- City Fajr Shuruq Duhr Asr Magrib Isha

- Dubai 04:20 05:42 12:28 15:53 19:08 20:30

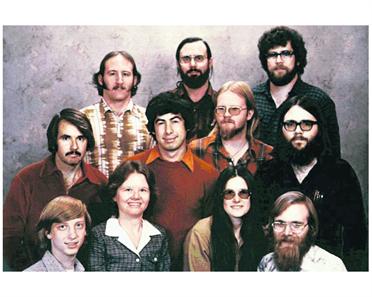

A 1978 photo of the 11 people who started Microsoft Corporation (AP/MICROSOFT)

When future historians put pen to paper, finger to laptop, or who-knows-what to who-knows-what device, Bill Gates will be up there as one of the most influential business leaders and philanthropists of the modern age, a John D Rockefeller for the turn of the 21st century.

Future generations will balance the monopolist against the philanthropist, the copycat against the visionary. With the specs, the jumpers, and the nasal voice, Gates was never going to pull off a Rockefeller-esque swagger, but this is, after all, the era in which the geek inherited the earth. He saw a new technology, shaped it, dominated it, milked it – and then quit to devote the rest of his life to giving it all away.

Yesterday, Gates retired from his day-to-day role at Microsoft, the company he founded 33 years ago. He is swapping, finally, the role of technology-industry pioneer and hard-edged business leader for a new role as the world's philanthropist-in-chief, spending his remaining days guiding the work of his $39 billion (Dh143bn) charitable foundation. It is, to be sure, a moment in history, and a moment to reflect that it is impossible to imagine our lives without Bill Gates. Without him, they would be completely different. Without Microsoft... well, what exactly?

There was always something about William Henry Gates III. Born on October 28, 1955, to a wealthy Seattle family, he spent all his spare time as a teenager fiddling with computers. He and his high-school buddy Paul Allen were captivated by the school's Teletype machine, which connected with a local computer, for which they wrote software. By the time he was 17, Gates had created a school timetable program that marshalled teachers and pupils, resolved clashes and magically, suspiciously steered a large number of girls into Gates' own classes. The school paid him for the program; whether the skinny, young-for-his-age Gates actually achieved any additional success with the girls as a result of his enterprise is not recorded.

A little over three decades later, and Gates is worth $58bn. For 13 years he has been the richest man on the planet, losing the title only this year after he started to hand money over to his foundation and watched the markets take down the value of his remaining Microsoft stake. Microsoft itself is worth $264bn, packing annual sales of $60bn. Its Windows operating system is the bedrock of almost all the personal and corporate computers in the world, fulfilling exactly the role that Gates famously predicted in his youth, mediating between the gubbins inside the box and the unsophisticated user at the keyboard, and opening up a world of technological possibilities. As the company grew through the Nineties, computer users queued around the block in major cities to buy each Windows upgrade on its release, as if it were a Harry Potter book or a coveted concert ticket.

In one of technology's most enduring feuds, Apple founder Steve Jobs fought Gates through the courts for years, claiming that Apple was the inventor of the style of graphical interface adopted by Windows.

Apple was the pioneer, sure, but Microsoft prevailed in claiming there was no copyright infringement. Both men had borrowed off earlier pioneering companies, Gates claimed, firing back: "Hey, Steve, just because you broke into Xerox's house before I did and took the TV doesn't mean I can't go in later and take the stereo."

Beyond Windows, Microsoft's word-processing software is ubiquitous (every article in today's newspaper will have been written using it, for example), its business tools a must for most big firms. The company's Internet Explorer is the world's most widely used window on the internet and Microsoft has even been carving out a piece of the net itself through its MSN e-mail and entertainment business, and through services for lucrative online advertisers.

Of late, its 30-year rivalry with Apple has bubbled back into life, with all those "I'm a Mac, I'm a PC" commercials adding a little piquancy, and it faces a challenge as never before from Google. But today, Gates is nevertheless handing over control of the broadest, most powerful technology company in the world. A company that has become too dominant, its critics still say.

The teenage Gates and Allen were pitched into an era where hardware and software development was proceeding apace, but in a disjointed way. Down in California, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were starting to bat around the ideas that would become Apple. But when a company called MITS invented the Altair, the first mass-produced microcomputer, in 1974, and advertised for hobbyists to invent a programming language for it, Gates jumped at the chance, set up a meeting for him and Allen – and only then scrambled to invent something. They were hired, and their work formed the basis of Microsoft, the company they founded the following year, with an impatient Gates dropping out of Harvard University to devote himself to the firm.

That was when Gates saw that future of "a computer on every desk and in every home". His was the genius to realise that a common operating system for computers would make them more useful for a wider range of tasks than seemed possible at that point in the Seventies. With this vision, he persuaded his Harvard pal Steve Ballmer to commit to the company as Microsoft's first business manager, and the two have been side by side at the helm ever since.

Gates sniffed the future – but he sniffed it with a hard business nose. That operating system would be valuable. It is the paradox at the heart of Microsoft, and the reason people debate whether the company's influence on the development of the PC market has been for good or ill.

George Colony, Chief Executive of the consulting firm Forrester Research, likens Gates to Thomas Edison, pioneer of the use of electricity in everything from the light bulb to the electric stove: "Unlike oil, pharmaceutical, or steel, monopolies are a necessary ingredient in the technology business," Colony says. "It's only when de facto standards such as Windows or de jure standards such as HTML become dominant that usefulness soars. Bill had the vision to see this future and he possessed the competitive drive to force his technologies into monopoly positions in the marketplace. "He has not been an innovator in technology – in polite circles we would call him derivative, in less genteel terms we would call him a plagiarist. Bill Gates has been a business innovator, not a technology innovator."

In 2000, a US judge ruled that Gates and Co had flouted competition laws in their five-year battle to establish Internet Explorer as the web's dominant browser and to crush the upstart Netscape in the process. The US ruling – stunningly – called for Microsoft to be broken apart, pulling Windows from the rest of the software business, but an appeal tempered the punishment.

Instead, Microsoft has been on a more-or-less bad-tempered probation in the United States and Europe ever since. The European Union just this year fined it a record €899m ($1.4bn) for failing to comply with demands that it open up its source codes to other developers – source codes that are the progeny of that primitive software Gates railed was being stolen by the hobbyists decades before.

The irony is that these days, Microsoft is as likely to be alleging competition law infringements by rivals [read Google] as it is fighting claims against it. The explosive growth of Google, which was barely a dorm-room computer project for founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page a decade ago, has created a rival dominating the internet as thoroughly as Microsoft dominates the market for software that comes in a box. Brin and Page have seen the future, too, and it is offering software that consumers and businesses can operate directly over the internet, rather than having to faff about installing on their computers.

Some bearish analysts in the tech industry even wonder if there is any growth in the future for sclerotic old Microsoft – which took five years to bring out a new version of Windows that has turned out to be barely an improvement on the last version, and whose belated attempt to compete with iPod, the Microsoft Zune digital player, has disappeared without trace.

As long as Gates has been the figurehead, it has managed to keep a semblance of geeky innovation in the corporate spirit, but observers fear an exodus of the company's brilliant scientists without him. It is a tricky time.

So it's the end, but the moment has been prepared for. Well prepared for. It is a full two years since Gates announced he would gradually reduce his commitments to Microsoft and gradually increase those to the charity organisation.

There is a bit of an end-of-term feel. A comedy video, recorded by Microsoft's bigwigs to entertain the crowds at the big consumer electronics conference in Las Vegas this year, parodies Gates's likely last day, in the style of The Office.

Gates has never been afraid to take the mickey out of himself. Yet the clip made a serious point, too. Ballmer ends by saying they will all miss seeing him in the hall every day, then turns to Gates as he exits with his belongings in a box: "Hey buddy, see you tomorrow at the board meeting."

The last thing that Microsoft needs right now, in these uncertain times, is for its visionary founder to walk off the set entirely. (The Independent)

![]() Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.

Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.