- City Fajr Shuruq Duhr Asr Magrib Isha

- Dubai 04:20 05:42 12:28 15:53 19:08 20:30

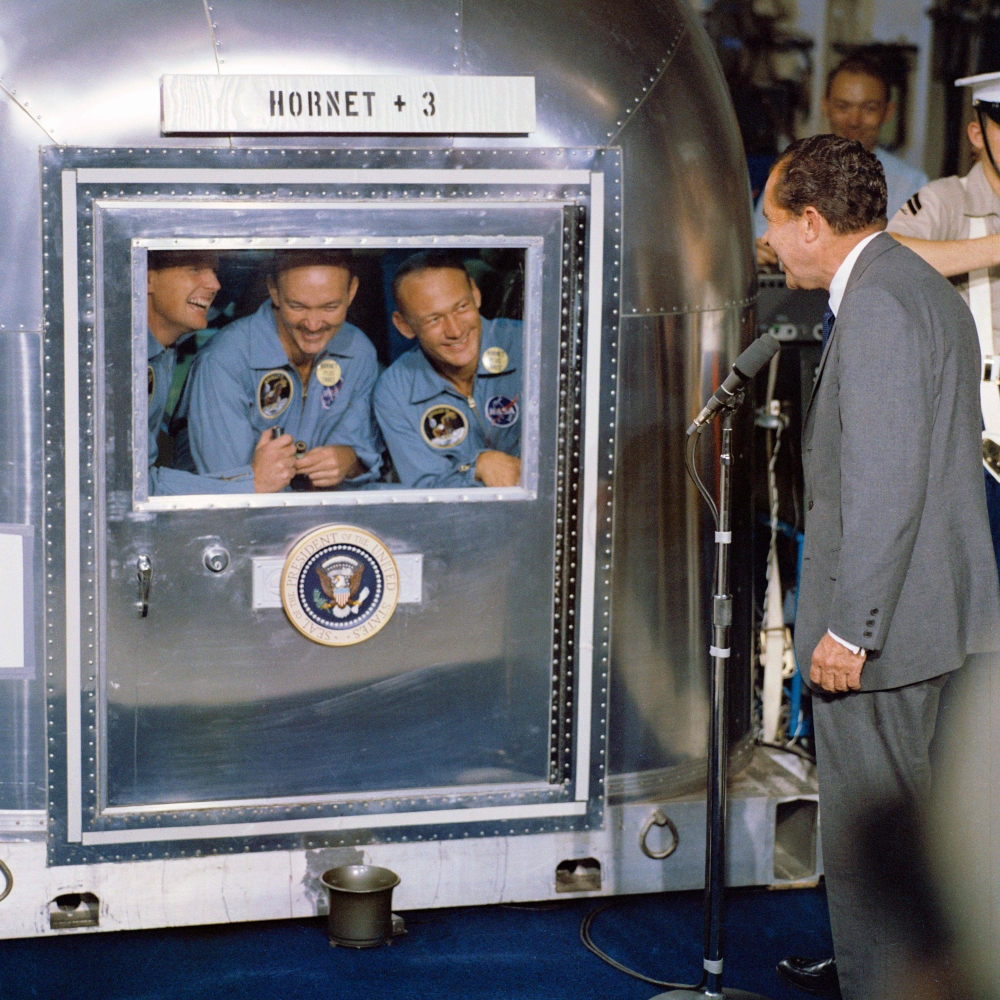

When Neil Armstrong walked on the Moon, he became the biggest live television star in history.

Officially more than 500 million people gathered around their sets to watch him leap from the ladder of Apollo 11's Eagle landing craft and onto the surface of the Sea of Tranquility.

But as AFP reported at the time, that figure was probably an underestimation.

Experts now believe the real number was closer to 700 million, a fifth of the planet's population at the time.

Next month will mark 50 years since Armstrong's famous phrase - "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind" - was heard around the world.

The moment was the culmination of an unprecedented 31-hour live link-up between NASA and major US TV networks.

Armstrong's first steps onto the lunar landscape on July 21, 1969 were followed second-by-second by viewers across the globe, with the notable exception of China and the old Soviet bloc.

Normal life across the planet stopped for those special moments, AFP reported, with Japan's Emperor Hirohito interrupting a ritual walk with his empress to watch it.

The mission was covered in exhaustive detail over a marathon eight days of broadcasts from the last-minute preparations and the lift-off, to the moonwalk and return to Earth.

Some 3,500 journalists followed events at the Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas.

'Astronomical' cost

Joel Banow, who was a director for CBS News at the time, said the sheer scale of the event was ming-boggling.

"It was my job to make the programme as exciting as possible. We spent more than $1 million on the production, which was astronomical for a news programme in '69," he told Robert Stone in his documentary "Chasing the Moon".

"Some of the ideas I came up with were inspired by science fiction films I saw as a child," he admitted.

In fact, TV channels competed with each other to come up with the most "space age" sets, with some turning to star sci-fi authors such as Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov and Orson Welles, the director of the radio drama "The War of the Worlds".

No fewer than 340 cameras captured the take-off of the Saturn V rocket from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, with a colour camera on board that could send images back live.

Photos: AFP

Every second of the mission was recorded by still cameras and tape recorders.

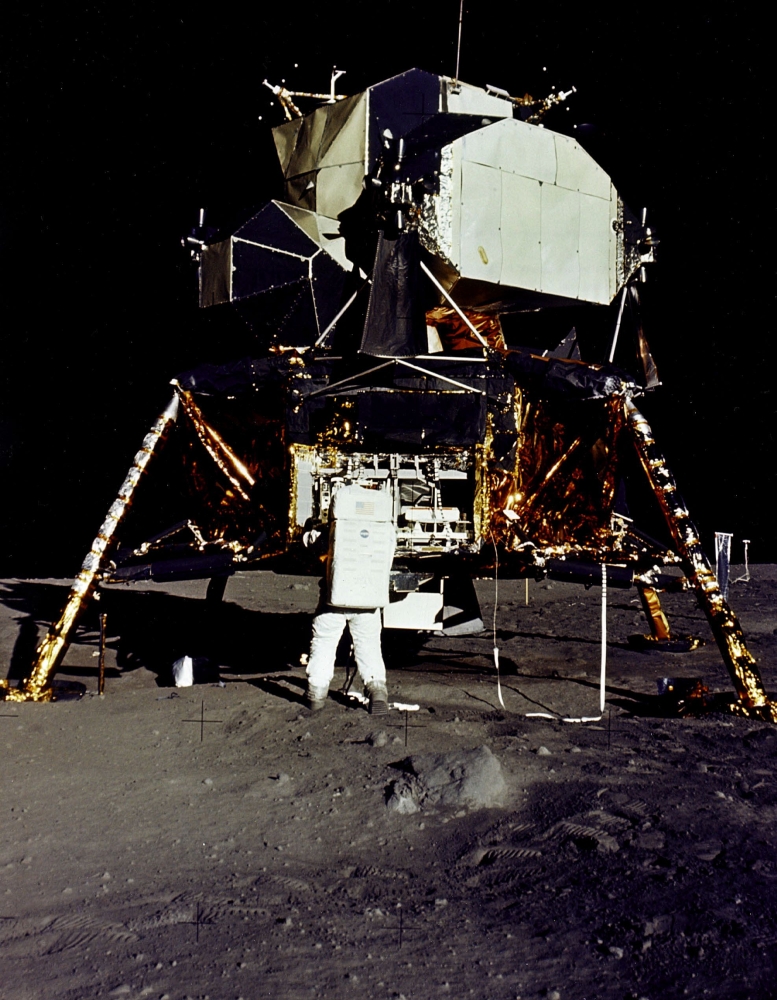

The Eagle had a black and white camera fixed to its exterior that began filming as soon as Armstrong opened the door of the lunar module, as well as a 16 mm still camera.

Fuzzy images

The images turned out to be rather fuzzy but very few people back on Earth seemed to worry.

"They had a ghostliness about them, you could almost see through the astronauts - the images were so slight to reduce the size of the transmission signal," said NASA's own television director Theo Kamecke.

The lunar landing - at the height of the Cold War and with the Vietnam war going against the US - was a huge demonstration of the technological superiority of the Americans.

"Apollo 11 was one of the least well filmed missions because the astronauts were not as well trained because the Americans were rushing to beat the Russians" to the Moon, said Charles-Antoine de Rouvre, the maker of a new French documentary on the mission.

Like many of his colleagues, he has been able to use never-before-seen images and recordings released by NASA recently.

"I always wanted to relive that night," he said. "People felt such intense emotions during those moments when everything stopped."

It was also the point when TV, with colour sets beginning to become more common, truly became popular, de Rouvre recalled.

With the astronauts looking back on the "Blue Planet", an image that would later help galvanise the nascent environmental movement, an iconic moment in human history was recorded.

"Everyone realised the importance of the moment and its symbolic power," de Rouvre said.

![]() Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.

Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.