- City Fajr Shuruq Duhr Asr Magrib Isha

- Dubai 04:20 05:42 12:28 15:53 19:08 20:30

For hundreds of years, we have been told what Newton’s First Law of Motion supposedly says, but recently a paper published in Philosophy of Science (preprint) by [Daniel Hoek] argues that it is based on a mistranslation of the original Latin text. As noted by [Stephanie Pappas] in Scientific American, this would seem to be a rather academic matter as Newton’s Laws of Motion have been superseded by General Relativity and other theories developed over the intervening centuries. Yet even today Newton’s theories are highly relevant, as they provide very accessible approximations for predicting phenomena on Earth.

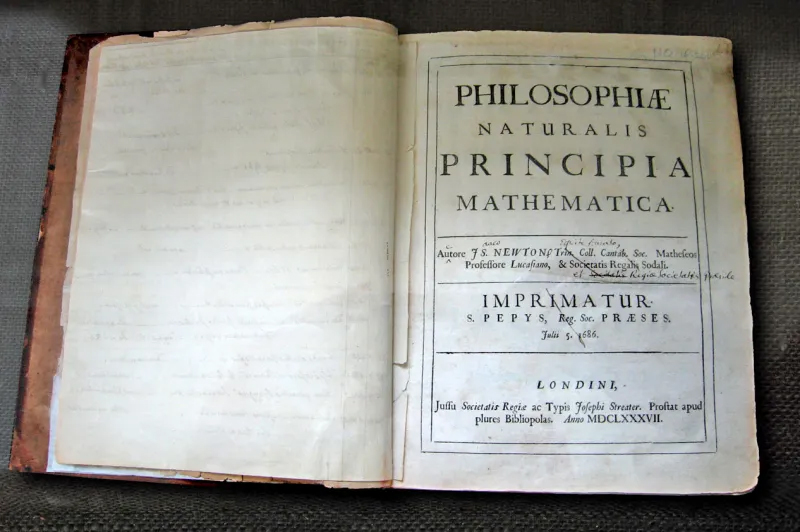

Similarly, we owe it to scientific and historical accuracy to address such matters, all of which seem to come down to an awkward translation of Isaac Newton’s original Latin text in the 1726 third edition to English by Andrew Motte in 1729. This English translation is what ended up defining for countless generations what Newton’s Laws of Motion said, along with the other chapters in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

In 1999 a new translation (Cohen-Whitman translation) was published by a team of translators, which contains a number of notable departures from the 1729 translation. Most notable herein is the change of the original (Motte) translation:

Every body perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impress’d thereon.

to the following in the Cohen-Whitman translation:

Every body perseveres in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by the forces impressed.

This more correct translation of the Latin nisi quatenus has significant implications for the law’s effects, as while Newton’s version does not require force-free bodies, the weak reading introduced by Motte’s translation incites exactly the kind of debate which has been seen over the centuries about why the First Law even exists, when in this translated form it automatically follows from the Second Law, rendering it redundant.

In the example of e.g. a spinning top, which Newton used in later elucidations of the First Law this follows as well, as a spinning top does not follow a rectilinear trajectory, yet it still maintains its spinning and other motions, unless disturbed by an external force (e.g. a hand touching it). Unfortunately, Newton never saw the English translation, as he died a few years before its publication, and thus was never able to correct this mistake.

The essential impact of this improved translation would thus be that we have to reconsider our interpretation of Newton’s First Law of Motion, along with the complexity of translating precise wording between natural languages which are so different.

![]() Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.

Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.