- City Fajr Shuruq Duhr Asr Magrib Isha

- Dubai 04:20 05:42 12:28 15:53 19:08 20:30

In July, as a political dispute in Washington threatened to cause a US debt default, the Central Bank of the UAE declared it had stopped investing in US government bonds “due to the very low return on holding these instruments”.

Four months later, with the dispute temporarily resolved and default avoided, the UAE Central Bank said yields had risen enough for it to resume buying Treasuries.

But as Western governments struggle with large debts and deficits, the incident showed how flows of Gulf petrodollars – for three decades, ploughed routinely into the West through lending and investment – are not as reliable as they once were.

By contrast, the Gulf’s trade and investment ties are expanding rapidly with Asia and other emerging markets, where economic growth is far outpacing that in the developed world.

This year’s Arab Spring political unrest is also prompting Gulf governments to focus a growing proportion of resources on their own region, in order to buy social stability.

“Capital flows around the world are changing,” said Shawkat Hammoudeh, a former economist with the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries who now studies petrodollar flows at Drexel University in the US.

He said the amount of Gulf capital available to the West was shrinking, in a process that could take many years.

SURPLUS

The US in particular depends on capital flows from the Gulf, where governments with dollar oil earnings and currencies pegged to the greenback have historically found it convenient to invest in dollar assets.

The Institute of International Finance banking association estimates that 55 per cent of capital outflows from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE – went to the US between 2002 and 2006. Eighteen per cent went to Europe, 11 per cent to Asia and 11 per cent to the Middle East and North Africa.

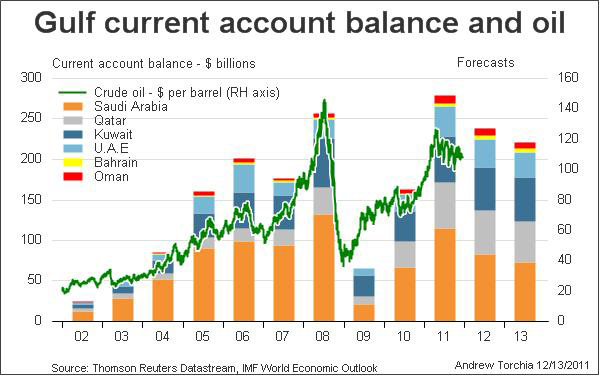

High oil prices and rising production mean the Gulf is awash in petrodollars this year; the GCC’s oil income will rocket to a record $608 billion in 2011 from $465 billion last year and $402 billion in 2009, the UAE’s Emirates Industrial Bank calculates.

The GCC’s current account surplus – the amount of money it has left to invest abroad after imports of goods and services – is expected to climb from $163 billion in 2010 to $279 billion this year and $238 billion in 2012, according to the International Monetary Fund. Such numbers put the GCC in the same league as China, which the IMF estimates will have a current account surplus of $361 billion this year.

Figuring out exactly where the GCC’s money goes is impossible, because Gulf governments, central banks and private investors are secretive. But there are signs that petrodollar flows into US assets are slowing.

US Treasury data shows holdings of US government securities by oil exporters – a group dominated by the GCC – rose just 8 per cent from $212 billion at the start of 2010 to $230 billion in September this year. Holdings by other countries among the top five investors rose much more steeply in that period: by 29 per cent for China, 25 per cent for Japan, a huge 103 per cent for the United Kingdom, and 22 per cent for Brazil.

Similarly, Asian oil exporters – another group dominated by the GCC – bought a net $2.4 billion of all long-term US securities, including equities and corporate bonds, in the first nine months of 2011. That was dwarfed by China’s purchases of $12.8 billion and Japanese buying worth $107.7 billion.

Those figures may understate the amount of GCC investment, which could be channelled via other centres. But data also shows that Gulf money held in US bank accounts has dropped slightly after rising steadily from $13.7 billion in 2003 to a peak of $129.9 billion in late 2008.

Hammoudeh said Gulf money also appears to have left some European banks this year as the euro zone debt crisis spreads from a few small countries to the core of the bloc.

At least some of the money leaving Western banks has been pulled back to the Gulf, bankers in the region say privately; commercial banks in most GCC countries have enjoyed strong deposit growth for much of this year.

INVESTMENT

GCC countries also invest directly in companies and factories abroad – to the tune of $36.5 billion in 2008, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development – although relatively little goes to the US and Europe.

A US Department of Commerce study found that 84 percent of FDI into the United States last year came from eight countries, none of them in the GCC. When FDI flows eventually revive, many are likely to go into emerging markets, with a big share to the Middle East and North Africa: inter-Arab FDI grew nearly twentyfold between 2000 and 2008, according to the Arab Investment & Export Credit Guarantee Corp.

“There is a shift from mature to emerging markets,” said Fabio Scacciavillani, chief economist at Oman Investment Fund, which invests on behalf of the Omani government.

Rising domestic spending in response to the Arab Spring will also limit how much Gulf states can invest abroad.

The IMF estimates new social welfare steps announced by Saudi Arabia this year, including construction of housing and hospitals, will cost $110 billion or 19 per cent of gross domestic product over several years. Hammoudeh said that would raise the break-even point in its budget – the oil price needed to ensure a budget surplus – from $66 a barrel to $88 over the past two years. Next year it will be $93, he predicted.

Scacciavillani said some of the GCC’s sovereign wealth funds were shifting their emphasis from simply investing petrodollars abroad toward “combining investment with domestic objectives” such as economic growth and technological development.

And the richest GCC governments are not only spending on political stability within their own borders: Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE have pledged at least $30 billion of aid over a number of years to Bahrain, Oman and North African countries hit by unrest, little of which has been disbursed so far.

Asked this week whether the Arab Monetary Fund, a regional group based in Abu Dhabi, might contribute to emergency international aid for the euro zone, Director General Jassim al-Mannai was clear about the Arab world’s priorities.

“There is a big need in Arab countries, a constant need, taking into account the Arab Spring,” he said. “Also, oil prices may drop because of weak economic growth ... I cannot see Arab countries could help Europe.”

![]() Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.

Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.