- City Fajr Shuruq Duhr Asr Magrib Isha

- Dubai 04:25 05:43 12:19 15:46 18:50 20:09

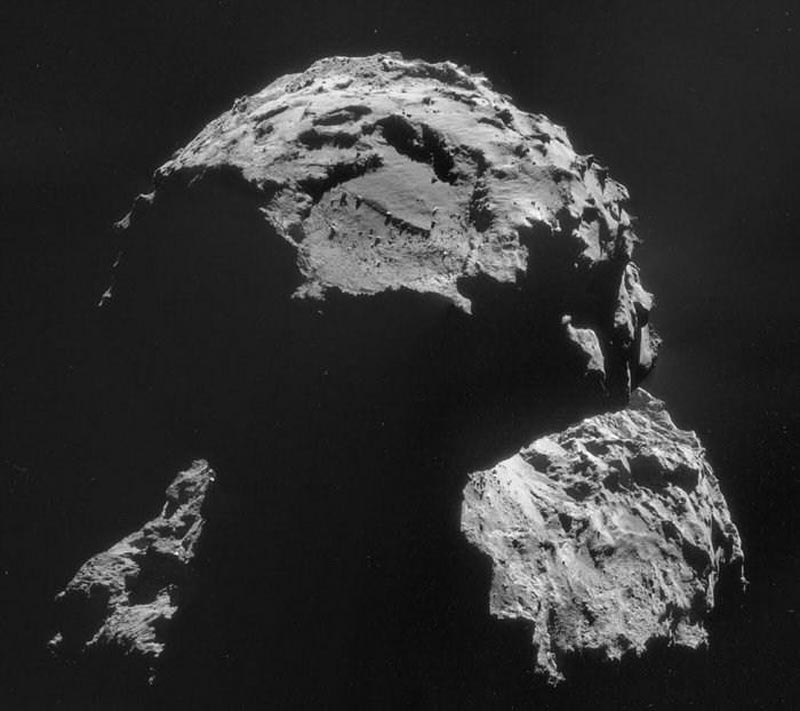

This image obtained from ESA on November 10, 2014 shows the Agilkia landing site on this image of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, taken with Rosetta’s navigation camera on 6 November, just days before its lander 'Philae' makes its historic descent to the surface. The image presented here is a mosaic of four individual NavCam frames, captured from a distance of 30.5km from the comet's centre on 6 November while Rosetta was en route to the separation trajectory from which it will deploy Philae on November 12. (AFP)

Europe's dream of landing a probe on a comet entered a crucial stage on Tuesday as scientists grappled with a roster of checks on the eve of the historic descent.

The European Space Agency's centre in Darmstadt, Germany, was to make four "go/no-go" decisions to press ahead with Wednesday's high-risk operation or abort.

Carried by the orbiter ‘Rosetta’, the probe ‘Philae’ is a 100kg lander carrying 10 instruments for the first-ever boots-on-the ground analysis of a comet.

If a hunch is right, Philae could unlock astounding knowledge about the origins of the Solar System and life on Earth, say astrophysicists.

The checklist was preceded late Monday by a brief moment of worry when Philae "took a bit longer than expected" to be activated, said Paolo Ferri, mission leader at Darmstadt.

"We were a bit worried at first that the temperature would be wrong (for the descent) but it all worked out. We didn't lose any time," Ferri said. "The robot's batteries should be charged up by tonight."

Philae has travelled 6.5 billion km on its mothership since the pair were launched more than a decade ago.

But the last 20km of its trek will be the most perilous of all.

That is the distance to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko that Philae must cover after separation, which is scheduled at 0835 GMT on Wednesday.

Touchdown will take place about seven hours later, with a confirmation signal expected on Earth around 1600 GMT.

But for all this to happen, Rosetta first has to perform a high-precision ballet, more than 500 million km from home.

Philae has no thrusters, which means Rosetta can only eject it when the velocity and trajectory are right.

A tiny inaccuracy means the error in its path will widen during the descent -- the probe could miss its landing site and smash into rocks or cliffs nearby.

"Failure is not an option," Philae scientist Jean-Pierre Bibring of the Paris-Sud University in France said Monday.

Early Wednesday, Rosetta will swerve inwards towards the comet and burn its thrusters, the final pre-ejection manoeuvre.

Scant time will be available to verify that these calculations are right before the "go/no-go" for separation is given.

Adding to the tension is the unknown surface of Comet "67P". It could be tough or brittle, soft or crumbly.

Fridge or feather

Philae will land at 3.5km per hour, firing two harpoons into a surface the engineers fervently hope will provide grip.

Ice screws at the end of its three gangly feet will then be driven into the comet, while a gas thruster on the top of the probe goes into action to prevent the lab bouncing back into space.

The size and heft of a refrigerator back on Earth, Philae will weigh just one gramme (0.04 of an ounce) -- or less than a feather -- on the comet.

One of the most complex and ambitious unmanned programmes in space history, the 1.3-billion-euro ($1.6-billion) Rosetta mission was approved back in 1993.

It took a decade to design and build, and after its launch, another decade to catch up with the comet, using the gravity of Earth and Mars as slingshots with which to build up speed.

Philae accounts for about a fifth of the haul of scientific data expected from the mission.

Its instruments include a mass spectrometer, a high-tech tool to analyse a sample's chemical signature.

Comets are believed to be primordial ice and carbon dust left over from the building of the Solar System.

They are doomed to circle the Sun, at orbits that can range from a few years to millennia.

According to a leading theory, comets pounded the fledgling Earth 4.6 billion years ago, providing it with carbon molecules and precious water -- part of the tool kit for life.

![]() Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.

Follow Emirates 24|7 on Google News.